Clarity for Product Leaders

Welcome to the final post in my mini-series on clarity for product people! In my previous blog posts, I have written about the importance of clarity in product collaboration and I’ve given actionable tips for how Product Managers can increase clarity on each of the four layers of clarity: directional clarity, situational clarity, role clarity, and clear communication.

Now let’s take a look at product leaders: the Heads of Product, Product Directors, VPs of Product, and CPOs. Obviously they also play a very important role in providing clarity and enabling successful product collaboration in their organizations.

In addition to all of the pointers I have already given for the individual contributors in my previous posts, product leaders have additional means (and additional responsibility) to equip their teams with the necessary clarity they need to collaborate and succeed together. This is one major way for product leaders to make a positive impact.

Let’s do a quick review of the four layers of clarity. For more detail, see each of the blog posts I wrote for PMs on each layer (I’ve linked to them above and I’ll also include links at relevant points throughout this article).

Directional clarity advice for product leaders

We need directional clarity so everybody can work independently towards a common goal. If we’re lacking directional clarity there may be a lot of action and busywork, but it’s not moving us forward.

In addition to the general thoughts on directional clarity from my previous post (getting started, asking three basic questions about clarity, developing a narrative in different formats, and repeating), here are some things that you as a product leader can and should do to provide directional clarity for your organization:

Create an interlinking cascade of directions by using the Decision Stack

If you have noticed signs that the rest of your organization is not clear on your direction, I would always recommend using the Decision Stack as a mental model to check if you have sufficient clarity at the different levels and if they logically interlock.

The Decision Stack is a mental model by Martin Eriksson that beautifully shows in the abstract how vision, strategy, objectives/goals, and specific opportunities/epics that you pursue build upon and rely on each other depend on each other and how product principles can guide your decision-making.

From the top down, you ask "How?": Objectives specify how we want to implement the strategy in the near future.

From the bottom up, you ask "Why?": We pursue certain opportunities because they are the most promising in contributing to the chosen objectives.

What I particularly like about the Decision Stack is that it also explicitly reminds us that deciding on a direction means saying no and that with every step of breaking down our direction, we also consciously decide what we are not doing.

Ideally, we also make our nos explicit for extra clarity—even if it will trigger controversial discussions. I have observed that too often we keep implicit what we have decided against to avoid discussions—and by doing so compromise clarity.

For instance our decision to focus on 2 initiatives that contribute to our objective to improve retention may mean that another potential initiatives that may have helped with acquisition will not (yet) happen. By making this explicit we risk a discussion with the head of growth, but increase clarity for anyone involved (and also provide a clarity that the head of growth can refer to when presenting his results).

By the way: Using the Decision Stack as a mental model does not mean that you will need an artifact that shows the whole cascade—or that you even have to explicitly refer to it.

If your organization is curious to learn about such mental models or finds confirmation in knowing that you are acting “by the book,” go ahead and share it. In many organizations, though, I’ve seen that only a minority care about our dear product frameworks and mental models—however great they may be—and it can be a better approach to just use them to guide your own thinking and express the results in words and artifacts that naturally fit your organization’s ways of working and talking. In other words, feel free to use mental models and share them when you find them helpful, but there's no need to belabor the point. Choose the level of detail that makes the most sense for your organization.

Reference & repeat!

Even if you have a logically connected cascade of directions, it may be that it is still not clear enough for the rest of the company.

It is therefore important that whenever you speak with colleagues from different departments, you refer to the consciously chosen direction so that it becomes ingrained.

So for instance: When talking about a particular initiative in an all-hands meeting, make it a point to say which objective it’s supporting or what its role is in the context of the broader strategy.

Or when you observe that within a team too much energy is spent discussing options which have no connection to the overarching direction, use it as an opportunity to ask the team how they understand the overarching direction and how their options connect to it. Either you will learn that they have connections in mind that were not obvious to you—or you can use this opportunity to bring the conversation back to the real priorities.

And more generally, as with the PMs: In case of doubt, it’s better to repeat your perspective one more time to increase clarity.

Clarify priorities (with or without OKRs)

As far as clear priorities are concerned, it is important that you always strive to clarify which objectives and goals are currently most important for the company so that your product teams know what to prioritize for. If everything is important, nothing really is.

In my experience, this can be a difficult exchange with other stakeholders in management, especially with senior stakeholders who believe that committing to clear priorities limits your ability to respond to changes in a dynamic environment.

But the opposite is true: Communicating clear priorities is a necessary foundation for allowing your cross-functional organization to pull in one direction. And if the context really changes in such a way that you need to change priorities, this needs to be a conscious act and communicated as such to bring the organization along with the change. Anything other than that will rightly be perceived as chaotic and indecisive management.

I have had good experiences with establishing a regular rhythm in which the goal priority is reviewed and challenged within your cross-functional management group. If you use OKRs, this is supported through formats like the mid-term check-in, but even if you do not use OKRs, you can only create the necessary clarity if everyone is clear about what is most important in case of doubt—and what is not.

Situational clarity advice for product leaders

Situational clarity is how you and your teams respond and act in the moment when you notice ambiguity. In my blog post on situational clarity for product managers, I already gave some examples for how to increase situational clarity by successful alignment, understanding how decisions get made, and managing conflicts of interest.

All of the recommendations above apply also for product leaders, so feel free to check out that blog post.

As a product leader, there are some additional things you can do to increase the likelihood of situational clarity in your organization:

Time-bound priorities complemented by long-term principles

We already discussed the importance of clear priorities as part of directional clarity, but obviously clear priorities are a necessary ingredient to help your teams gain situational clarity for themselves as well as the people they work with. And as a result, clear priorities increase decision speed.

The ideal here, in my view, is a "forced rank" prioritization where it's clear which goal or project has priority over others. This is used very consistently, for example, at Zalando, and a friend who is a Product Lead told me that it also makes negotiating collaborations very straightforward: “Is your project a higher priority than what I am otherwise currently doing? OK, then I'll help you now.”

I think it’s clear that getting to a company-wide forced rank prioritization is challenging, but I believe it’s worth the effort and would have helped me massively in my work as a product leader in contexts where we didn’t have such a clear hierarchy of priorities.

In case you find it impossible to push your organization to such company-wide priorities, you can still aim to put priorities for your area of influence in a clear order. Not only will this help your teams, but it can also lead to substantial conversations with your managers about what’s really important.

While priorities will change over time (hopefully accompanied by transparent communication), it makes sense to complement them with more long-term product principles as additional guardrails for your team’s day-to-day decision-making.

As we’ve seen above, product principles are also one of the elements in Martin Eriksson’s Decision Stack and he has described this concept in detail in his talks (such as his 2022 mtpEngage Hamburg talk).

Typically, product principles are a set of four to six "THIS over THAT" pairs. A popular example is Amazon, whose principle is to prioritize the B2C experience over the B2B experience when in doubt. It’s easy to imagine how this can help their teams to make otherwise difficult trade-off decisions.

I recommend that you develop product principles with a group of product colleagues across different levels of experience to create buy-in and use them as an opportunity to strengthen your organization’s identity for how you want to work.

When you do this, you will likely encounter proposals for product principles that sound nice and that everybody can agree on—but that won’t help with your teams’ decision-making because they just manifest the obvious or common sense.

As an example take “Build what’s relevant to customers over just following the latest trend” : Sounds good, doesn’t it? But now ask yourself if any sane team member would ever consider the opposite.

When working on your product principles, try to identify less obvious pairs and look for crisp wordings that can be easily memorized. To help your team connect them to their day-to-day context, aim to provide three to four examples per principle that illustrate what applying this principle could mean in practice.

Here’s an example for that:

JOB SEEKER OVER RECRUITER

- Solutions that result in direct messages to job seekers are relevant to them and feel personally written - even if it means more work for the recruiter.

- Ask job seeker only for data that improves their experience instead of asking for additional data points that we will only use to create fance recruiter dashboards.

- Provide the best selection of job offerings possible - even if it reduces the visibility of job offerings recruiters pay us for.

With a set of clear priorities and product principles, your team will be well equipped to create situational clarity and come to decisions easily and quickly.

Clarify responsibilities

Another important way that product leaders can help their teams create clarity in the moment is by clarifying responsibilities. Especially in larger endeavors, you can often run into the issue that although many people are involved, no one feels responsible for driving the project forward. We will discuss this further in the section on role clarity below.

Role clarity for product leaders

Role clarity is important to ensure that everybody involved knows what to expect from each other and how they contribute to the collaboration. There are some ways PMs themselves can increase role clarity, for instance by clarifying role expectations within their teams and by clarifying roles and who makes decisions in (larger) collaborative efforts. I have written about this in my blog post on role clarity for PMs.

As a product leader there are some additional things you can do to ensure more role clarity:

Define clear competency profiles and coach accordingly

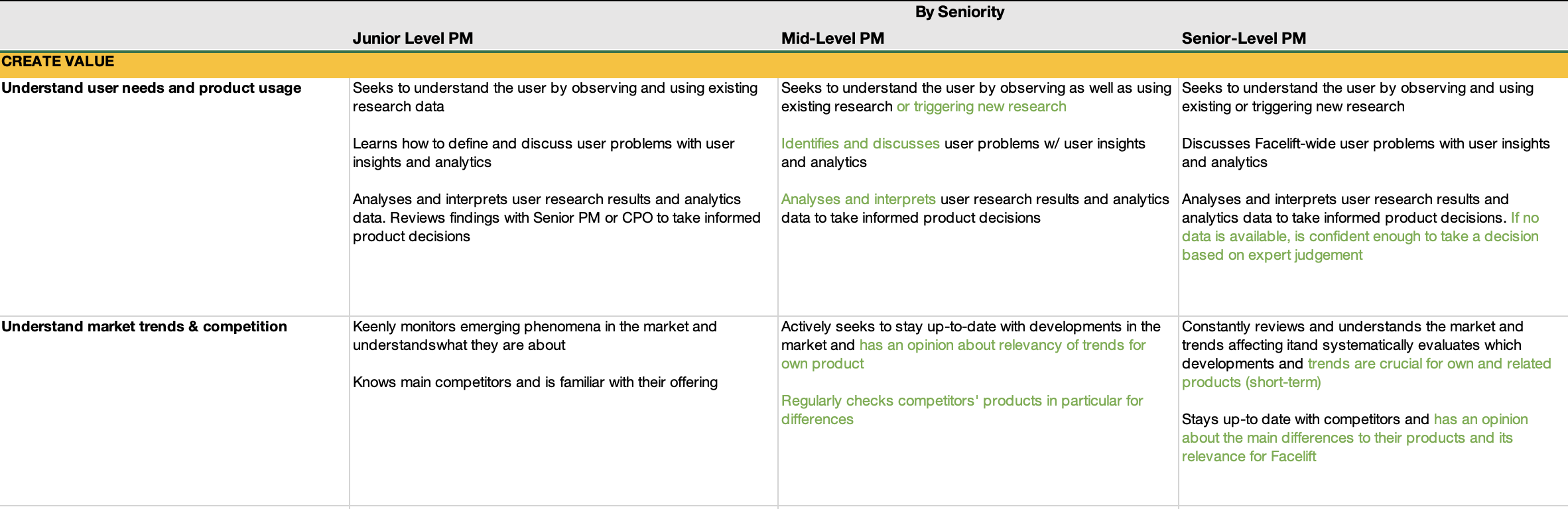

One obvious contribution you can make to role clarity is that you can define clear role descriptions and competency levels for each role on your team. These competency profiles should differentiate what’s expected from a role on different levels of experience and indicate how the expectations of a senior PM differ from those of a mid-level PM, for example.

I have had good experiences with structuring the competencies by a set of primary expectations of that role, irrespective of experience level. For instance for my team at Facelift (B2B SaaS) I used the following dimensions:

- Create value

- Provide direction

- Assure clarity

- Deliver results

- Collaborate effectively

I would then break these into relevant sub-dimensions that still apply for every level. For instance, for “Create value” I used the following sub-dimensions:

- Understand user needs & product usage

- Understand market trends & competition

- Analyze

- Validate

Next, I would describe what competencies I would expect for each of these dimensions from a junior PM, mid-level PM, and senior PM. I would indicate changes from one level to the other with a different color code so that you can clearly see what competencies set apart a senior PM from a mid-level PM.

Here’s an example of the resulting table for two sub-dimensions of “create value.”

(Side note: While it’s not shown on this table, I think it’s important to emphasize regular, direct interaction with users as a necessity for all PMs).

It’s important not only to clearly explain this competency framework to the PMs, but also how you intend to use it. For instance I made the following points:

Depending on a PM’s specific context, they may not need to use and demonstrate all expected capabilities.

This system is meant as a foundation for ongoing development dialogue, not as a system of boxes to tick in order to progress to the next level (a common misunderstanding with ambitious PMs!)

It's OK that within one's seniority level not all expectations are (yet) met equally well. And even if they are, it does not mean that there’s no room for further growth.

The model described here was a good fit for a product organization with around 8 PMs and we used a similar logic when I worked at XING with around 60 PMs.

The larger the organization gets, the more likely you are to have more different levels of PMs and product leads. In his talk “Great Expectations” at the mtpEngage Leadership Forum, Thor Mitchell shared that Miro decided on a total of ten levels. Larger organizations may have even more levels for which they describe the necessary competencies.

You can find an interesting overview of PM career levels at different companies at levels.fyi.

But make no mistake: Having a system of competency levels in place is only a foundation for assuring role clarity. While it’s helpful to have this written down to create a shared understanding—especially in larger organizations with more than one product leader—it is equally important for the product leaders to be in a constant dialogue with the PMs, identify gaps they still have, and coach them accordingly. This does not mean that you will have the competency framework in front of you for every 1:1, but it serves as a framework that you can implicitly or explicitly refer to from time to time.

If you want to learn more about coaching as a product leader or a manager in tech in general I recommend three books:

Petra Wille’s Strong Product People with specific advice for any product leader

Michael Bungay Stanier’s The Coaching Habit about the right mindset for coaching

The Trillion Dollar Coach - a book about the famous Silicon Valley coach Bill Campbell

Assign clear responsibility

Another task for product leaders is to clearly assign responsibilities and decision-making powers for larger, cross-team initiatives. In my post on role clarity for PMs I have taken the position that PMs must not wait for their leadership to assign responsibilities and can take a clarifying role.

The more direct and more reliable way to assure that everybody knows who’s driving an initiative is for the product leader(s) to assign responsibilities from the beginning. I’ve observed that this can be tricky because it can essentially mean that you need to pick and assign a “primus inter pares” (single out one person from a group of people who are hierarchically on the same level, such as three senior PMs involved in a cross-team initiative). But if you don’t do it this way, you take the risk that people will step on each other’s toes or that nobody will take the lead. So it’s in your best interest to provide clarity on whom you expect to drive a joint initiative—and who’s expected to contribute.

There are various frameworks that can be used for this, but personally, I find DACI (Driver, Approver, Contributor, Informed) most suitable in the product context because the term “Driver” beautifully expresses that there should be EXACTLY ONE person ultimately responsible for moving things forward and making decisions if necessary.

As the product leader, you will typically be in the “Approver” role. This means that you need to spend time with the Driver to set the right decision criteria so that ideally you will not have to intervene. Intervention by the Approver will weaken the driver and can also send the whole group into another change curve because they will likely already have aligned with the Driver on the joint direction.

If you see the need to intervene as an Approver, you should ask yourself if you have been as clear as you could about your expectations. And also challenge why you decided to pick the Driver you picked and possibly learn for future occasions.

There’s a natural tendency to pick folks who most strongly voice their opinion or those with the longest tenure, but neither of the two criteria are guarantees that this person will be a good Driver of a joint initiative. In the end, their ability to create directional clarity and situational clarity, for instance through collaborative alignment, matter more.

Clear communication for product leaders

As I’ve explained in my blog post on clear communication for PMs, all levels of clarity are interlinked and depend on each other, but clear communication is a crucial ingredient for any type of clarity.

All points in that blog post (taking responsibility for making yourself understood, providing context and orientation, clear writing, intentional presentation of data, and listening to understand) also apply for product leaders. Here are a few additional tips for product leaders specifically:

Double down on giving context and orientation

In particular, giving context and orientation will be very important for product leaders because you usually have more highly visible opportunities to do so. In particular it’s the product leader’s responsibility to actively reference the overarching direction of particular initiatives to establish an understanding of coherence of product direction.

Don’t get me wrong: This does not mean that you always need to refer to a fully fledged overview of vision, strategy, objectives, etc. Instead, it’s the continuity of relevant and actionable references that help the rest of your organization understand the direction and how they can contribute.

Provide clear framing

As a product leader you can massively contribute to the clarity of communication if you actively provide framing. For instance there is a high risk of ambiguity whenever leaders give feedback or ideas and leave their team speculating how that feedback was intended: Is it an order to change things? Is it a consideration we want them to assess further and provide another suggestion? Or is it just another data point and the team’s free to use it if they find it helpful?

In this example the product leader can increase clarity if they not only give their feedback but also say how they expect the team to use it.

Be flexible in your communication modes

Every product person benefits from being able to communicate their plans and the direction for their product in different contexts (short elevator pitch, data-driven stakeholder presentation, simple but impactful update in company all-hands, etc.) and from consciously looking for different modes to tell the same message—with words, data, using metaphors, or diagrams.

As a product leader, this is particularly important because you’ll communicate in a broader set of contexts (for instance, to supervisory boards or to external audiences), your presentation carries more weight, and you set the tone for how well your PMs adjust their communication to different contexts.

The starting point for adjusting your communication to different contexts is to prioritize your listener’s understanding over your own time and to actively think about how what you want to share is relevant to your audience: What’s in it for them?

It can also help to look into the art and craft of storytelling (see Petra Wille’s advice on this), but you will also need to adjust your storytelling to the typical style of communication in your organization and consciously decide on good moments to break out of the (potentially boring) average style of communication by applying more inspirational storytelling.

Translate between stakeholders and the product development organization

As a product leader you will usually have more interactions with your organization’s main stakeholders in other functions (the CEO, commercial leaders, etc.) which puts strong emphasis on your ability to translate among those different stakeholders and back and forth between the stakeholders and the product development organization (Product & Tech). Ideally you will have a strong tech counterpart who can help with this as well.

As a product management nerd, one of the lessons I had to learn the hard way is that most people outside product management just don’t care about our terminology and our frameworks. They only care about the results and the impact this has on their area of responsibility. This means they can best understand the implications if you use terminology they are familiar with.

So instead of trying to educate your management peers about the latest product lingo, make an effort to understand what matters to them and the terminology they use to talk about it. If you take responsibility for translating with care, you don’t risk your message getting lost in translation.

The other direction of translation is that when speaking with your PMs or to your broader product development organization, you help them understand how the growth targets the CEO talks about or the monthly sales performance report translate into their terminology and mental models. With regards to the PMs, it’s worth helping them become good translators themselves so that in their day-to-day interactions with customer success or support teams, they can make themselves understood more easily.

Contributing to a clarity-friendly organization: Safe and curious!

Lastly, I want to point out that as part of your organization’s leadership team, you can not only influence clarity directly by how you act and communicate, but also by contributing to the general clarity-friendliness of your organization.

By clarity-friendliness, I mean to which extent the everyday culture in your organization makes it easy, safe, and ideally rewarding for anyone pushing for clarity to do so. This is strongly influenced by how you and other leaders in your company behave.

A simple example is how you respond if somebody asks a clarifying question in a larger meeting. Even if you are surprised that the colleague asks this question because you feel they could or should already know the answer, it’s important to not ridicule the person daring to ask the question and instead applaud them for giving you the chance to clarify this.

More broadly, this also comes down to psychological safety as a necessary foundation for clarity. Creating clarity means stepping up and exposing yourself in ways that people may not immediately like.

In a culture in which people on different levels of the organization don’t feel safe to speak up, it is much more likely that people will accept ambiguity rather than step up to create clarity. And if this happens in many situations, it poses a serious risk to successful collaboration—as well as to your product’s and your organization’s success. I assume that most readers will be familiar with the concept and the general importance of psychological safety for successful tech organizations. If not, this HBR article is a good starting point.

But it’s not only important to create a culture in which people feel safe to step and fight for clarity. It’s also important to promote a culture of curiosity.

Curiosity is important because whenever you clarify something it means that you or somebody you collaborate with will be surprised, will learn something new, and will be challenged to adjust their view of things. This can be exhausting or even painful and the natural reflex of folks may be to oppose or become defensive, which in turn makes the life of those fighting for clarity much more difficult.

This is why it really helps if the culture of your organization supports a mindset of curiosity for constant learning and for seeing surprises and new perspectives as a learning opportunity. In reality this will of course also depend on the individual mindset of your employees, but as a leader, you can set a positive example by actively showing that you are curious to learn about new perspectives and you’re ready to adjust your view on the path to more clarity.

Final thoughts

With this post, I’ve looked into some specific aspects on how product leaders can and should commit to clarity in their organization and how they can collaborate to succeed together.

I have referenced my previous posts on clarity for product managers because many of the recommendations for PMs also apply for product leaders. But there are some aspects that product leaders should keep in mind because of their role, their leverage, and their responsibility:

I hope you found this post and/or my mini-series on clarity for product people helpful. I would be glad to hear your perspective and additional thoughts in the comments!